I’ve been blessed throughout my riding career with very few injuries to my horses. But this summer my riding and show plans were ended by an injury that my horse managed to get while on turnout in a group.

My horse, Bogart, is a 16-year-old Dutch warmblood, a former jumper who has been doing low level dressage work with me for seven years. As soon as I brought him in that day, I knew something was wrong. He wasn’t tracking up at the walk, and there was the swelling at the back of his right hind leg that ran halfway down the cannon and around the fetlock joint. The vet came and did a lameness exam, flexion tests, ultrasound and X-ray. Bogart was diagnosed with a small tear to the suspensory branch. He was classified as a 4 out of 5 on the lameness scale, which means “lameness is obvious at a walk.”

Given my lack of experience with such injuries, I did what many horse owners would do – I panicked. But the treating veterinarian was patient and explained in more detail what I was dealing with. In the interests of this article, I’ve chosen to publish Bogart’s ultrasound images in order to clearly illustrate what the injury is.

The handsome patient, Bogart, pre-injury. (courtesy Kim Izzo)

Suspensory ligament injuries are fairly common, particularly in racehorses and show horses, given the amount of strain their legs are placed under. As is the case with humans, the ligaments in horses attach to the bones and act as support during movement. The suspensory ligament is a thick and fibrous structure that attaches to the back of the cannon bone just below the knee on the front leg or below the hock on the hind leg. This is known as the origin of the suspensory. About midway down the cannon bone, the ligament divides into two branches which insert into the sesamoid bones on the back of the fetlock. Luckily for me, Bogart’s sesamoid bones were normal.

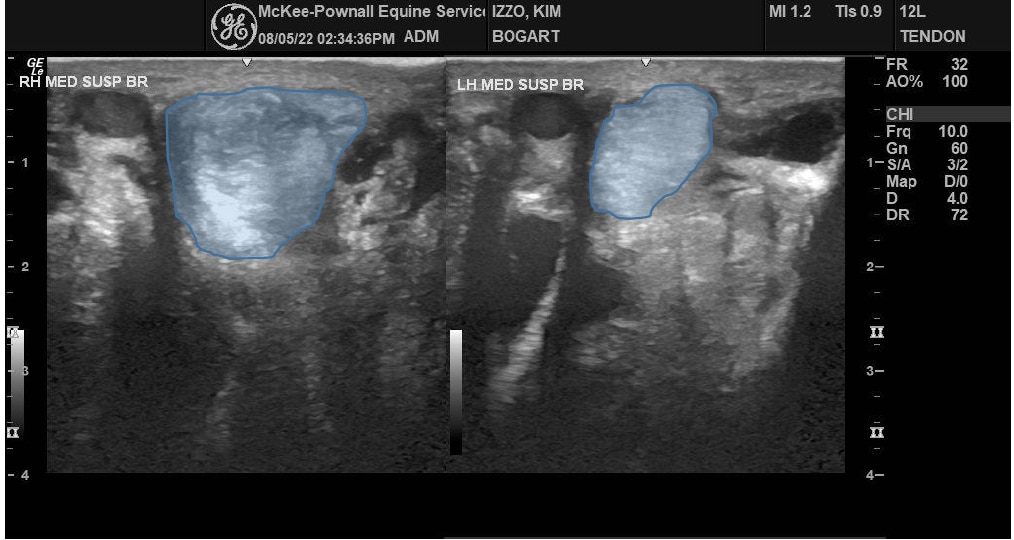

I spoke to Dr. Kate Robinson (who is not the veterinarian who treated Bogart) about branch suspensory injuries and how they are diagnosed. “We look at three main things when assessing a tendon or a ligament injury,” she explains. “The first one is if we see any areas of black within the tendon or the ligament [imaging]. Black on ultrasound is fluid and so that means there’s a complete disruption of the fibers or the structure in that area; this would be the tear.” (See Fig. 1)

Fig. 1: Longitudinal view of the right hind suspensory branches (image at left). The RH medial suspensory branch is overall larger than the lateral (left hind image at right) with a less defined linear fibre pattern, and a specific area of pattern loss (highlighted in red).

The second thing that the vet will study is the ligament on cross-section, which is when the probe cuts across the leg instead of up and down. “On both cross-section and longitudinal section, we’re also looking at the size of the structure and we’re comparing that to the “normal” scan on the sound leg,” she says. “The size of the black area or tear is an important thing that we assess and measure.”

The size is measured to compare to published normal cross-sectional area measurements (as well as the opposite uninjured leg); the larger the ligament is vs normal, the more severe the injury. The size helps to determine prognosis and a treatment plan.

The third thing that the vet will examine on the ultrasound is the fiber pattern of the ligament. “The best analogy that I have heard is that normal structure is like knife-straight lines,” Dr. Robinson explains. “Or if you think of uncooked spaghetti held in a handful – long, tight, and straight lines is what a normal suspensory branch should look like. When we have an injured branch, we see what we call an abnormal fiber pattern or a decreased fiber pattern.” (See Fig. 2)

Fig. 2: Cross-section near the top of the RH and LH medial suspensory branches, illustrating the difference in size and lack of organization affecting most of the length of the RH branch.

There might be sections or a section of the suspensory branch, where there is loss of those lines, or they are wavy, and it’s that loss of linear pattern that’s an indicator of injury. “And so that paired up with the other things that we’re assessing on ultrasound, as well as our clinical assessment of the horse is really what helps us to grade or categorize the severity of the injury,” she adds.

The treating veterinarian told me that Bogart’s prognosis wasn’t career-ending, but it would disrupt our summer. It would be 6-8 weeks before I could begin a long slow rehab program. Such rehab programs are case-specific and vary depending on the severity of the injury, but it’s typical for a program to take about 12 weeks from start of under-saddle work until full work is resumed. This will also depend on how the horse responds to the program and if there any setbacks.

Summer riding was a write-off, but I do feel optimistic that Bogart’s (and my) riding career is far from over and I can’t wait to return to something as simple as walking under saddle.

The Latest