Training the canter-trot transition is essentially the same throughout the horse’s training, but as horses develop the collection necessary for canter-walk or canter-halt transitions, what becomes important is differentiating your aids for the canter-trot. Problems with the canter-trot transition can arise as the horse develops the collection in the canter; the key to prevention is correct training of the aids for canter-trot, as well as reinforcement of that transition throughout the horse’s career.

From the knee

My horses learn from the very beginning in the canter that when I relax their backs a little and then close my knees, they are to drop into a trot and keep thinking “forward.” Closing your knee into a downward transition is a very basic signal that a three-year-old horse will understand. If your knee is open and your leg is relaxed and draped on the horse, the horse knows to go forward. If you close your knee against the horse, it will respond by stopping or slowing down.

Once horses learn to collect and perform canter-walk transitions and eventually canter pirouettes, it’s important that they continue to understand the difference in aids for the canter-trot transition. For canter-walk or canter-halt I think of making the horse sit into it, while for canter-trot I think about making the horse relax into it. In the grand prix test, you have the canter pirouettes – the most collected of all the canter exercises – almost immediately followed by a trot transition. By relaxing your seat and opening the thigh and then closing your knee, you are telling the horse to relax in its back and go forward into the trot. I always relax my seat and thigh a little bit before closing the knee for the trot. As long as I continue to ride the trot transition slightly differently than the walk or halt transition, my horses learn to recognize the distinction. They know that when I relax my seat and let them out of the collection, they can expect a possible canter-trot transition.

Shoulder-fore on the circle

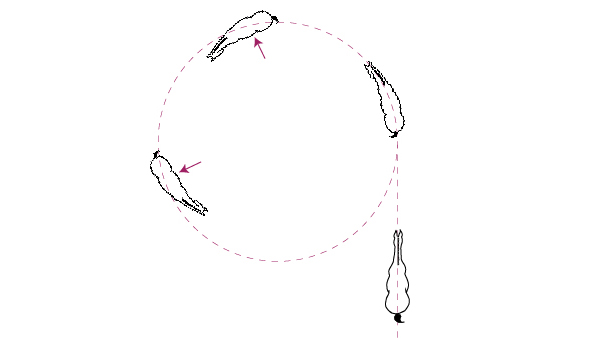

When I’m working with a horse that wants to just collect the canter instead of trot, the answer is to ride into a shoulder-fore position on a circle before asking for the transition to trot. As I ride the shoulder-fore, with the haunches toward the outside of the circle, I want to feel that I am pushing the inside hind leg toward the outside. I’m not trying to keep both hind legs active, only the inside leg. In the shoulder-fore position, I then close my knee to ask for the trot, while continuing to use my inside leg to keep the horse’s inside leg active and to maintain the direction of energy going from my inside leg to outside rein. It’s keeping the horse’s inside leg active that makes the trot transition available again. This exercise is not about inside bend, but about the feeling of the horse leg-yielding away from the driving inside leg. It’s not only about going forward, but also a little bit sideways at the same time.

The shoulder-fore on the circle exercise becomes another means to teach the horse to recognize an upcoming canter-trot transition. I don’t believe that rote practice of the transition always at the letter in the ring where it happens in the test is of value. I should be able to access that transition anywhere, at any time. However, with all my FEI-level horses (that are at the level where they can do canter pirouettes, which means the canter-walk or -halt are also established), I rarely ride canter-walk transitions. Once the horse has the collection needed for the canter-walk, I always ride canter-trot transitions. I do my canter work – such as half-passes, flying changes and pirouettes – and then at the end of the canter work I put the horse into a shoulder-fore position and then into trot. After the transition from canter to trot, I balance the horse, and then go into extended trot, the sequence in most FEI tests. This is how I end my canter work, every single time, every single day.”