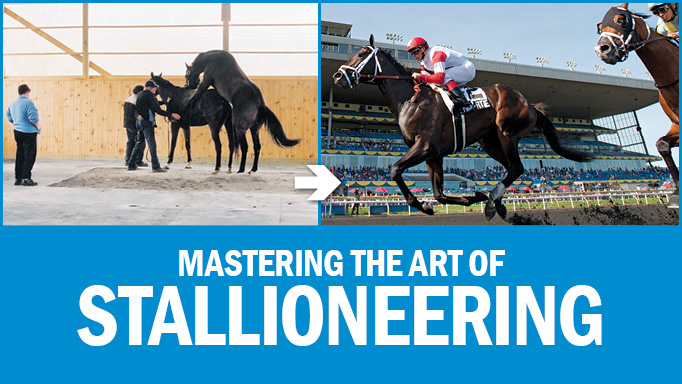

What happens in the breeding shed, tends to stay in the breeding shed. Until now, that is, as Canadian Thoroughbred recently sat down with a pair of veteran stallion handlers, Shannondoe Farm’s Arika Everatt-Meeuse and Gayle Bosscher, breeding division manager for Colebrook Farms, about their experiences in developing future winners.

Everatt-Meeuse was raised in the business by her parents James and Janeane Everatt and has been in charge of matings for Shannondoe Farm of St. Thomas, ON for more than 20 years. An accomplished rider, who owned her first pony at the age of two, she quite literally grew up on the back of a horse.

In 1970, Bosscher became the first female to show a stallion at the Royal Winter Fair, taking honours in the Canadian Hunter Stallion category with Toreador. She is now a key part of overseeing a Colebrook stallion roster at the Uxbridge, ON farm that includes Where’s the Ring, Eye of the Leopard, Signature Red, Leonnatus Anteas, Badge of Silver, Not Bourbon, Bear’s Kid and Nonios.

“I’ve always seemed to get along with stallions,” said Bosscher. “I just bonded with colts and snotty mares over geldings. Because I started in the hunter game, I always worked with thoroughbreds.”

While Everatt-Meeuse and Bosscher have very different backgrounds and responsibilities at their respective outfits, there’s one thing they both agree on when it comes to breeding horses.

“Rule number one is you have to stay safe,” said Bosscher. “I’ve worked with stallions my whole life, I’m 64 now, and the only time I’ve ever been hurt in a stallion shed was when someone pushed me out of the way, thinking I was about to be in trouble.”

When working with 1,100-pound animals, each guided by its own unique temperament, there’s bound to be some trouble along the way. Everatt-Meeuse recalls one troublemaker in particular, the productive stallion Varick, who was really quite a handful.

“Varick was a Mr. Prospector horse and probably the most lethal horse I’ve known. You couldn’t leave a tub or water bucket around or he’d rage. He threw a lot of tough horses,” said Everatt-Meeuse. “He was different. All of a sudden he would kick a stall. He took the whole front off a stall one day. Once he decided it was happening, you couldn’t stop him.

“Varick did not like men, but he got on just fine with my mother and myself. If someone handling him tried to be aggressive, he would get you. He’d wait and he would savage you.”

Perhaps it’s that experience that has led Everatt-Meeuse to hire, for the most part, other women as part of a breeding team that includes Kelly and Ashley Bako, Thomasina Orr and a pair of weekend students.

“A lot of these girls ride and I think if they’ve been on top of a horse and can ride at a certain level, they understand what makes them move. From up there, you definitely have a better idea of how a horse thinks,” said Everatt-Meeuse.

The Birds and the Bees

Generally, breeding season begins around Feb. 15, but the timeline can vary if a mare comes into heat sooner than normal. With a gestation period of 11 months, horses conceived in February will be foaled in January.

Each stallion farm has a particular process for breeding horses.

At Colebrook, the stallions are turned out and given a chance to ‘be a horse’ early in the day before their first breeding appointment which might start at 11:30 a.m. The breeding shed includes a garage door-type system that keeps the mare and stallion separated while each animal is prepared for their ‘date.’

Breeding is big business with stallion fees at Colebrook ranging from $2,500 to $5,000, and the value of the mares brought in for breeding can fluctuate greatly in price which means not only do you need to keep your workers safe, you have to keep the horses safe as well.

“The mare comes in and the door by the wash bay area is shut while we get the mare ready. We do the tail up and wash her up for breeding. We make sure she is completely ready before going to the shed,” said Bosscher.

At the same time, the stallion is being readied for business.

“We take him to the door where he can see the mare and trust me, when he sees the mare, he knows why he’s there,” Bosscher said, laughing. “The stallion stands there until we bring them out. He’s not allowed to be rank and has to wait until the mare is teased and ready to breed.”

Finally, before the mare is brought to the stallion, she’s fitted with boots to protect both parties in case she decides to kick. At other farms, mares can be fitted with all types of safety equipment including shoulder pads. The whole process, which is recorded, takes about 20 minutes. The arrangement can be clinical and, surprisingly, often occurs with the mare’s foal from the last breeding season in tow.

“I believe the mares are more comfortable when their foals are near them,” Bosscher said. “So, we have a person who stands in front of the mare with the foal and the foal is kept out of harm’s way.”

Stallion Training for Conquest Curlinate

This year, Everatt-Meeuse will be charged with bringing recently-retired racehorse Conquest Curlinate to the breeding shed for the first time. Among the favourites for the Queen’s Plate in July, he was injured when sideswiped by another horse during morning training just days before the $1 million classic.

Now the young stallion prospect will begin a different type of training and when you consider that his famous father, Curlin, currently stands for a fee of $100,000, it shines a light on the importance of a stallion handler’s role.

“He’s younger than any of the other stallions. First we need to make sure he’s sound after stall rest and rehab. Then we test breed him and check fertility. For that, we use a mare that has been covered many times and shows good heat and will stand well,” Everatt-Meeuse said.

The goal is to teach Conquest Curlinate good manners in the breeding shed.

“We teach him to wait. Mother Nature will come in at a certain point when he’s ready. He’ll know how to jump up on a mare, but you have to teach him to wait for when the mare is ready,” she said. “It’s no different than any other training. You want him to come out and wait for you to allow him to get closer. You don’t want him bolting at the mare.”

A tall fellow, Conquest Curlinate should have no trouble with jumping up on a mare, a decided advantage over stallions that are smaller in stature, such as the world famous Northern Dancer, who sometimes required a mare to stand in a gully to accommodate the breeding.

Another key factor, one that both Everatt-Meeuse and Bosscher agree on, is that you have to keep your stallions happy.

“Certain stallions may only like a certain paddock,” said Everatt-Meeuse. “You might think he wants to be in a big five-acre grass paddock but then the horse walks the fence.

“You have to pay attention, you don’t put him back out there tomorrow. If he wasn’t happy, move him around. We’re very accommodating and always trying to keep them happy and to me that’s important for their overall condition.

“Ulcers and foundering are huge things in this industry. You have to really pay attention to their body condition and day-to-day lives. They have to be happy and healthy… and you need to have luck.”

Reward is Results

It’s hard work, but for Everatt-Meeuse, the reward is in the results. This past year, Shannondoe’s first crop sire Society’s Chairman, with limited numbers, produced multiple stakes winning filly Caren as well as the promising Code Warrior who captured the Golden Nugget Stakes, at Golden Gate.

“Conquest Boogaloo and Conquest Daddyo (both bred by Everatt-Meeuse and her parents) were important as well as I got to see my first horses run at the Breeders’ Cup. It’s exciting for me. We’ve been blessed with a good year,” she said.

And if all goes well in February, both farms will be blessed with another crop of racing’s future stars.