“In many ways the world of the horse constitutes the epitome of social decorum, not only in the age of chivalry…but in our own time as well, when forms of dress traditionally associated with equestrian activity…are considered appropriately stylish for those who have never sat upon a horse.” ~ Man and the Horse: An Illustrated History of Equestrian Apparel, Mackay-Smith, Druesdow and Ryder (1984)

Nothing about horse sport is quick or easy. Any equestrian can attest to the hours behind every second of competition, and choosing your #rootd is really no different. There’s something magical in finding that perfect combination of boots, breeches, shirt and jacket, the ideal mix that is both comfortable and presentable, allowing for a myriad array of activities (Mucking stalls! Cleaning tack! Chasing your dog out of ring two!) while still looking traditional.

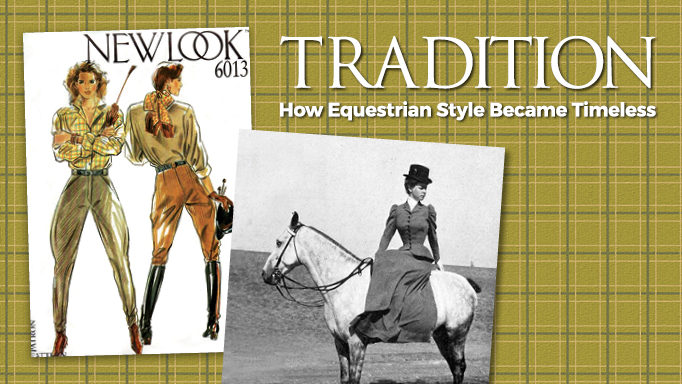

There it is, that word we equestrians all know so well: traditional. Whether you’re riding or watching it, what you wear for this stuff really matters, doesn’t it? Not only are there soft social rules (“I don’t care what the judge said – you will NOT remove your jacket,” said every trainer ever), but there’s often even a hard dress code. You can’t rock up to Ascot with a bare head, and attempting to show a hunter while wearing a bright jacket would probably give someone an actual, lethal heart attack.

Who among us doesn’t have a story about that time their trainer dragged them to the shops to buy exclusively long-sleeved shirts (it’s all about the cuff, am I right?) or became personally affronted by an untucked shirt or a lack of hairnet? Why is that? Why do we fiercely protect the silhouettes, colours, and styles of our horsey past? And why do mainstream fashion houses continue to borrow from our playbook?

To Whom We Owe the Velvet Collar

To fully understand our love affair with – and stubborn refusal to change – equestrian fashion, we need to look back on how we got here and what the things we wear to ride say about us, our sport, and the equestrian lifestyle as a whole.

Our relationship with the apparel needed for equestrian endeavours is as long and complicated as our relationship with the horse itself. The British, of course, had a lot to do with it. They helped lay the foundations of most modern equestrian sport; foxhunting led to show jumping, hunters, and equitation, which you can thank for all the black and navy (and the odd velvet collar) you’ve sported in your life. They’re pretty much responsible for importing polo from India and starting a worldwide craze for it. They straight-up invented the Thoroughbred, and thus modern racing as we know it.

Military influence was naturally huge; after all, the majority of British military presence involved extensive cavalry units, and these are the folks who pretty much wrote the book on colonialism. Therefore, from the 18th century, braiding and cords in gold and silver became popular in civilian riding habits, as well as shoulder decoration and ornamental fastenings. We still see remnants of this trend today in stock tie pins and embellished or crested jacket buttons.

On another level, though, the British imparted social and economic markers. Foxhunting, polo, horseracing – these were sports of the elite requiring substantial land and expensive in both time and money. Equestrianism earned (and especially at the top end of the sport, still maintains) its label as a luxury endeavour.

Form, Fabric, and Function

Regardless of wealth, however, equestrian clothing has always needed to be a blend of useful and durable; it is, by nature, a predominantly outdoor sort of thing, and fabrics needed to be sturdy enough to endure strenuous activity, while the cut had to accommodate a wide range of movement. In fact, in the early days of riding sport, one’s riding habit routinely cost more than a ball gown and was expected to last several years. Natural and yet steadfast fabrics were favoured; wool, tweeds, leather, and waxed canvas might not have been the cheapest materials, but they were needed to provide longevity.

Style features were also specific and important: the single vent in the back of men’s tailored jackets evolved to divert rainwater off one’s tack, and even in the days of sidesaddle, ladies could purchase so-called “safety skirts” which claimed to be less likely to become caught up in one’s tack in the event of a fall (and absolutely still sound like the least safe thing ever). The classic jodhpur silhouette, with voluminous thighs and tight calves, originated in the ancient state of Rajasthan, India, to provide chafe-free mobility for the growing-in-popularity sport of polo. Honestly, though, as much as I love a vintage look, I’m not mad at stretch fabrics for essentially killing off the jodhpur. That was a hard shape to look cute in.

Interestingly, as the horse became less about locomotion and more about leisure and sport, what we wore to ride, and when, could have easily been relaxed. We don’t technically need to compete in tailored jackets or collared shirts; I mean, you don’t see many other sports rocking a shoulder pad at the Olympics these days (which is sort of a tragedy, because everyone looks better with a shoulder pad, not sorry). Yet our attachment to traditional dress seems absolute. Just ask your trainer if jackets are waived one more time if you doubt this. We really don’t need to, and yet we hold fast to these traditions. They mean something to us, they reference the past, and perhaps, they even reference the equestrian lifestyle itself.

Timeless Elegance

I’ve heard a lot of opinions chalking our love of traditionalism up to a blend of nostalgia and general poshness; it’s easy to dismiss the look and cost of modern riding apparel as an urge to look minted. And yet, to describe the deep respect we equestrians have for traditional styles and silhouettes, as well as the widespread influence of equestrianism in fashion as a whole, as nothing more than a bid to look cool, seems to fall a bit short.

Sure, people like luxury, and aspirational fashion has always been popular; and yet equestrian fashion permeates popular culture in a way that other luxury sports do not. Race car driving, professional golf, tennis, squash, and fencing are all considered to be less-than-attainable in terms of time, talent, and cost, and are often referred to as luxury sports – and yet we don’t see Formula One tracksuits or pressed golf khakis or white fencing jumpsuits being appropriated for the runway, or mixed into stylish attire as a statement piece.

Equestrian apparel is more than just attractive to equestrians; it’s a timelessly elegant aesthetic that the general population is drawn to time and time again. Especially Ralph Lauren, for like, the entire ‘80s. He was really into it.

Rituals and Routine

Equestrianism, I think, has an undeniable, inescapable hold on us, because it combines everything we find interesting and seductive about luxury and decorum with some of the most simple, most primal feelings possible, feelings that resonate with us all. A horse is a way from point A to point B, literally, but figuratively as well. A horse is a way out, a way up; it is speed and sport and partnership and adventure. A horse gives us what we lack, while only asking our compassion and care in return. A horse is freedom.

Sure, it costs – but the horses don’t care what we pay to buy them, to keep them, to train them. They’re the perfect blend of the purchased and unownable; the race that’s never entirely won, the job that’s never done. They’re a labour of love, of passion, of constant struggle.

Perhaps the aesthetic behind that resonates with everyone, because everyone gets that, you know? Maybe everyone wants to be a little fancy while also working hard towards something that can feel well-earned. Maybe our allegiance to traditional equestrian fashion has less to do with fashion and more to do with horsemanship; unwavering attention to detail, to repetition, to doing something correctly and often. Good horsemanship is essentially a series of rituals and routine; constantly checking and rechecking the smallest of things can make all the difference. Tricks and tips and knowledge passed down from generation to generation, done the same way, over and over again.

A psychologist friend of mine once told me that the ultimate marker for hopelessness was when someone stops performing small acts of decorum in their life – setting the table with the good cutlery, folding the laundry, pouring the wine into the nice glassware occasionally. These little actions were taught to us by those who came before us, as they were taught before them. Small, everyday traditions that make us feel ready, organized, at home.

Sometimes, when I’m hand-walking my horse or checking a hoof for heat or polishing my boots, I think about this. I think about the things that I’ve been taught, the small rituals I do over and over again, the fierce love I have for identical stable wraps and a perfectly-fitted hunt coat. All these things I care so much about, that I want to do, and keep doing, as long as I can. The actions that keep me hopeful, that keep me happy. Maybe that, more than anything, is what tradition is all about.